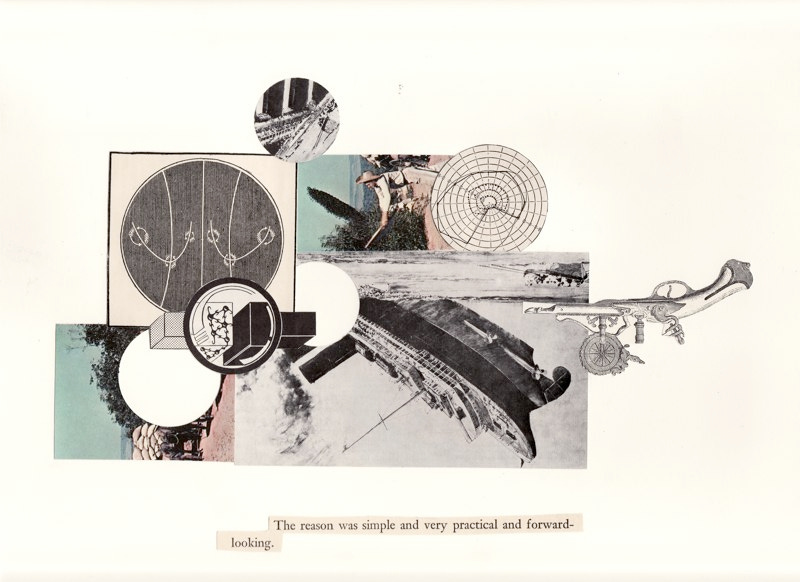

Pablo Helguera (Mexican, b. 1971) | The reason was simple and very practical and forward-looking from The Arlington Heights Suite, 2004-05 | Collage on paper

I visited the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago earlier this month, three days before I moved my life east. Wandering around with two of my friends, I came across this piece, relatively small and flat in an exhibition filled with sculpture and scale. The work is one collage in a series of more than 60 titled The Arlington Heights Suite, a reflection on the artist’s time in the eponymous suburb of Chicago.

I remember walking up to the piece in its corner and feeling struck by the title and the first sentence of the placard next to it: “This collage by Pablo Helguera combines fragments of the collective knowledge of mid-twentieth-century suburban life.” Helguera created the collage from pages of old textbooks purchased at used bookstores throughout Chicago, using education as a conduit through which to view the culture creation of American suburbia. “This guy was emo about living in the suburbs and made art about it,” I thought, amused and amazed.

Helguera describes Arlington Heights as “a quiet, harmonious non-place.” In 1516, Sir Thomas More first penned the word “utopia,” stemming from a bit of wordplay in Greek: ou-topos means “no place,” and eu-topos means “good place.” In many ways, the suburbs perfectly exemplify the oxymoronic concept of utopia: created to carry out American ideals of freedom, individualism, and prosperity, the suburbs became a failure of form, their sprawl furthering environmental degradation, segregation, and isolation.

I, too, am emo about living in the suburbs. My visit to the MCA came at the tail end of a holiday season in my hometown of Orland Park, Illinois, about an hour’s drive south of Arlington Heights. Helguera contrasts the generic qualities of the American suburb—the chain restaurants, stores, advertisements, cars—with the specificity of the memories stemming from the lived experience of growing up there. For me, thinking back to my childhood involves thought processes full of contrasts. My values are inherently opposed to the excess and ignorance of suburban living, and yet that is the way of life most familiar to me.

I lived in the same house from the time I was five months old to the time I moved out at 18. Most of my residual memories from that period come during its most impactful time, when I was a student at Carl Sandburg High School. And many of my memories from that era are shaped by my time as a competitive distance runner on the Cross Country and Track teams.

I’ve written before about the types of misogyny, homophobia, and prejudice that flourished on the team, mainly in this piece for NBN Mag my freshman year. These experiences shaped my version of Helguera’s collages—that is, my view of the collective knowledge of 21st-century suburban life. A trust in institutions, distrust of “others”, bootstraps mythology; For me, as you may have noticed, a lot of that collective knowledge took on a negative valence.

Removed from the monotony of the suburbs and moved to the absurdity of DC, my daily runs provide an escape, as they always have. Here, another mental contrast takes hold: Although many of my worst high school memories come from the insults of teammates, the support of the team led to some of my most powerful positive habits today. I’ve never run with my phone or with headphones, qualities instilled in me since the sixth grade, when I first joined my high school’s cross country camp. Because of this, running becomes a meditative experience, nothing but me and my body moving through the world around me.

My home in DC is located about half a mile from the Piney Branch Trail Head, an unmarked spot next to the 16th Street Bridge with some picnic tables and a wooden railing leading to the convergence of two single-track trails. Running here, as I do several times a week, allows me to immerse myself in nature in much the same way as I did at the Swallow Cliff trails back in the suburbs. Running over the gnarly, rocky root-filled terrain engages my senses in a way that running on streets and sidewalks simply can’t. Scrambling up muddy embankments, jumping over creeks, swinging my arms to balance on an inches-wide trail, I feel in touch with my body and the natural world in a unique way.

I don’t know if I can ever completely reconcile the emotions I feel about my upbringing into a neat, coherent narrative. Nonetheless, I look for grounding in the through-lines I can trace back to it, and of those, running is by far the clearest. Although it was by no means perfect, from 6th grade onward, the Carl Sandburg cross country team instilled in me values of humility, dedication, community, compassion, service, and plenty of others that I have adapted to align more with the way I live my life as a young adult.

Helguera finds a sort of peace in the ubiquity of the suburbs, “to visit its stores that could be anywhere in the US.” His mother’s apartment, he writes, acted as “some kind of sanctuary” within that environment, familiar and filled with memories. I feel exceptionally lucky to have found my own sanctuary hopping through the mud among grey oaks and thorny undergrowth, an experience formed among the forest preserves of the southwest suburbs of Chicago but readily translatable to the extensive parks and trails of the District of Columbia.